We are in the middle of a delightful floruit of queer science fiction and fantasy. Finally—finally — no single book has to be all things to all (queer) readers. No longer does the sheer relief of finding a novel with a queer protagonist (or several) predispose me in that novel’s favour. No longer do I feel compelled to highlight a novel’s good points and pass lightly over its flaws because at least it exists. I can finally be picky, and enter wholeheartedly into a criticism uncomplicated by the worry of contributing to a silencing of queer voices.

This is perhaps bad news for my reaction to The First Sister, Linden A. Lewis’s debut space opera novel from Gallery/Skybound. Billed as the first volume in the First Sister trilogy, it sets itself in a future version of the solar system occupied by two competing factions (one based on Earth and Mars, one on Mercury and Venus), with wildcard posthuman smugglers and water miners in the asteroid belt (the so-called “Asters”, viewed as subhuman by the two competing factions) and mysterious machine intelligences hanging out somewhere in the Oort Cloud. But where once the novelty of multiple queer protagonists in a reasonably well-drawn, well-written SFnal future might alone have spurred my enthusiasm, these days I have the luxury of expecting more.

Which leaves me in ambivalent position. Because there’s the bones of an excellent novel underneath Lewis’s The First Sister, a novel with the potential to engage deeply with questions of autonomy, power, and consent, and the queering—in multiple senses of the word—of bodies and identities. But those bones are thoroughly buried by The First Sister‘s rush to embrace dystopia without committing to a full reckoning of its horrors, and its inability to fully connect the personal with the political.

Questions of autonomy, power, and consent—sexual, bodily, medical, mental and otherwise—are dense, layered things. They’re ubiquitously present in human and social relationships: they bedevil us at all levels between the intimately personal and the globally political. (Your romantic partner makes more money than you: your neighbouring country intends to dam a major river to build a hydroelectric powerplant.) To grapple with those questions requires grappling with the way in which social and cultural trends reflect on the possibilities open to the individual, both in thought and in action. Lewis’s The First Sister—unlike another recent debut, Micaiah Johnson’s The Space Between Worlds — lacks the ability to link the individual and the societal on a thematic level, and loses a great deal of power thereby.

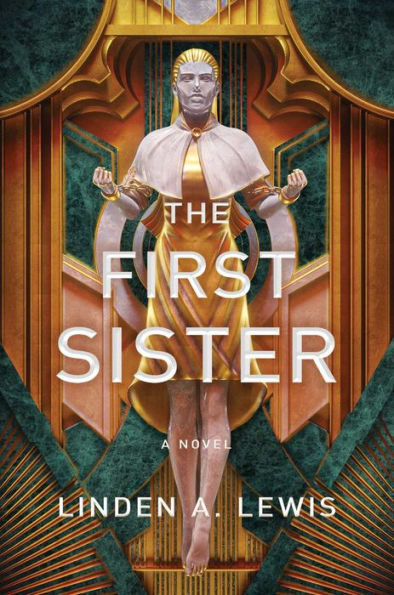

Buy the Book

The First Sister

The Geans and the Icarii are at war. The Icarii are a society than valourises scientists, and have more advanced tools than the Geans and access to better materials. Despite class prejudice based on the status of original settlers, limited social mobility is possible, and the Icarii have a universal basic income for their citizens, religious toleration, and what appears to be a functioning, if corrupt, democracy. The Geans, as depicted, are strongly militaristic and have a state religion, whose major figures rule alongside the Gean Warlord at the head of their state. What we see of them makes it reasonable to refer to Gean society as a totalitarian state.

The Sisterhood exists as part of the Gean state religion. Sisters are essentially comfort women with an additional religious “confessional” component, who are denied the ability to speak. Whether or not they wish to become Sisters appears to be nearly irrelevant: their consent while they are Sisters, not relevant at all.

Lito sol Lucius is an elite Icarii soldier in his early twenties. Hiro val Akira, his nonbinary partner—partner in what appears to be emotional as well as professional terms, though whether or not their relationship is sexual is never made explicit—has been separated from him and sent off on a mission following a military debacle that they both barely survived. Now Lito is informed that Hiro has gone rogue, and his new mission is to hunt down and execute his old partner.

Hiro and Lito are two of the novel’s three protagonists, though we see Hiro primarily through the lens of the long explanatory letter that they send Lito, and which is intercut with Lito’s point of view. This letter is much less an explanation and much more—in terms of its structure, theme, and content—a cross between a love letter and a suicide note. The primary emotional core of the novel is thus between the two poles of Lito and Hiro, and between the yearning for the emotional fulfillment of their partnership in service to the Icarii military and the betrayal of that partnership-in-service, either by Hiro or by the military itself. Lito’s narrative journey is one of discovering that the society he so desperately struggled to excel in—boy from a poor neighbourhood made good—is not worthy of his loyalty. (Though one wonders at his lack of cynicism at discovering the dark underbelly of medical experimentation and exploitation to his society, and his rapid about-face in going from seeing the exploitees as disposable to seeing them as worth protecting. Lito is, astoundingly, surprised to realise that the game is rigged and he’s been played.)

The eponymous (and paradoxically nameless) twenty-year-old First Sister is the novel’s other protagonist. We first meet her on board the Gean warship Juno, where she has been the departing captain’s favourite and thus protected from the other crewmembers: she expects to leave with that captain, who has apparently been promising her retirement into a countryside concubinage, and is gutted when she learns it was all a lie. It was a pretty pointless lie, on the captain’s part, since First Sister served at his pleasure regardless: this introduction serves to establish that First Sister doesn’t enjoy her job, wants quite desperately to leave it, and has remarkably few strategies for surviving in it.

The new captain of the Juno is a war hero ransomed back from the Icarii. Saito Ren is young, with two prosthetic limbs, and under suspicion. First Sister’s religious superiors want her spied on. If First Sister doesn’t get into Ren’s good graces and bring back information, First Sister will be demoted down the ranks, or perhaps killed. If she does as she’s told, she might get promoted to be First Sister of a whole planet—and no longer need to perform sex work on demand with random soldiers. But as the captain of a warship, Ren no less than First Sister’s religious superiors has First Sister’s life in her hands.

Although the novel, and the series, is named for First Sister, her narrative role feels somewhat secondary to the emotional drive that powers Lito’s arc and the tangle of connections between him and Hiro. This is in part due to the novel’s failure of imagination in terms of its religious worldbuilding and its failure to deal pragmatically with forced sex work, and in part simply because First Sister’s goals and relationships are less active.

To take the religious worldbuilding first: there is no sense that religious belief or practice is a live, meaningful thing within the oppressive religious institution that raises pretty young orphan girls to join the ranks of its comfort-woman priestesshood. There’s no sense of First Sister’s role as a sacramental one, and no tension between her religious duty and her personal preferences: it seems that all aspects of her role as a Sister are an unwelcome imposition that she feels no religious conflict about rejecting, or not living up to. Her concerns are primarily secular.

The First Sister avoids—with a near-prudish insistence—dealing pragmatically with the practicalities of First Sister’s role as a tool for the sexual relief of soldiers. To choose not to depict rape directly is a worthwhile choice, but to depict a society with the rape of priestess-comfort-women as a cultural norm and then to shy away from showing aftermaths, coping mechanisms, recovery; to have a protagonist who avoids being public property by lying about her status, and yet to never show the quotidiana of repeated trauma, or stealing joy in the face of suffering… Look, having a lot of sex you don’t want to have is terrible, and rape is terrible, and both of these things are unfortunately common, but The First Sister makes forced (religious) sex work a central part of its worldbuilding and is then squeamish about showing people coping with that.

(Aftermaths, coping, and recovery are far more interesting to me than suffering or striving to avoid it: the world is terrible and yet we must live in it, and make what peace we can.)

The narrative’s unwillingness to reckon deeply with the religious aspect or the pragmatics of sex work mean that First Sister’s interactions with Saito Ren, and First Sister’s choices concerning Saito Ren, come across as shallow, unrealistic, and underdeveloped. It’s hard to believe that First Sister is forging a real connection with Ren, even falling in love with her, when the narrative engages only on the surface with the invidious layers of power, both religious and secular, at play. The game of spies should be compelling, but falls short.

The crux of the plot hinges on a plan to assassinate a religious leader and install a different one in her place: to replace a bellicose religious head with a less gung-ho one. This is, allegedly, a step on the way to peace—though the novel’s politics are both labyrinthine and underdeveloped compared to the emotional bond between Hiro and Lito and First Sister and her desire for a new career, so perhaps peace is a lie.

That I have written an extended critique upon The First Sister should not be read as an indictment of the novel itself. Lewis has a strong voice, a good grasp of action, an eye for the cinematic rule-of-cool (empathically-linked duellists! mechanised battlesuits!), and the ability to sketch interesting characters. It’s an entertaining novel in a promising world (albeit a world whose structures I have a nagging urge to question): an enjoyable queer space opera romp with a dark underbelly.

But it’s so firmly focused on personal betrayals, personal angst, personal trauma, familial links and quasi-familial betrayal, that I can’t help but feel it leaves a sizeable missed opportunity in its wake. For it could have connected its personal questions of autonomy and consent to it social context: taken that first emotional reaction—these things are bad!—and asked, then, why do they happen? What function do they serve? What can be put in their place for less harm and more benefit? and how do we get from here to there?

Taking up that opportunity might have elevated The First Sister from enjoyable to excellent. But not all debuts can do as much on as many levels as Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice or Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, or even Micaiah Johnson’s The Space Between Worlds. The First Sister might have disappointed my highest hopes, but Lewis has made a promising start, and I look forward to seeing where she goes from here.

The First Sister is available from Skybound Books.

Read an excerpt here.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, was published in 2017 by Aqueduct Press. It was a finalist for the 2018 Locus Awards and was nominated for a 2018 Hugo Award in Best Related Work. Find her at her blog, or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council, the Transgender Equality Network Ireland, and the Abortion Rights Campaign.